|

| Trail overlooking Emerald Lake in Ceres Park. |

Have you been to Ceres Park? Tucked away in the woods on the southern side of our community is a quiet nature sanctuary and retreat featuring a network of primitive trails. It's perfect for meditative walk, an off-road bike ride, or a forest ramble with your (leashed) dog. Lakes, cliffs, a creek, and unusually steep hills give intriguing variety to the place. It's a lonely spot most times, but a hundred and fifty years ago it was the bustling, noisy operations center of a high-tech company that forever changed the state of New Jersey. In this post we'll take a moment to remember how things were back in the day. But first, some background information to set the scene.

A Forest from River to Ocean

When European settlers came to the area that is now our township they found it heavily forested with pine and oak--not the scrubby types that make up the Pine Barrens, but prime building timber. The first mills built were sawmills, and many a log from the banks of Mantua Creek eventually found its way to England: to London to frame a house, or to Chatham dockyard to build a ship. To the south in Cumberland and Salem Counties, where trees were smaller, settlers still found uses for them: cord-wood for heating or charcoal to help supply the growing glass industry.

As the woods became cleared land across West Jersey (which we think of as South Jersey today) settlers began to farm. They found a rich topsoil had accumulated in the former forest, leading to plentiful harvests. This attracted interest, and more people relocated to the area. Agriculture became an attractive opportunity. Boats full of grain and produce made their way down to the creeks to the Delaware and up to the growing market in Philadelphia.

Going West, Young Men

The sudden bonanza in agriculture was too good to last. Nutrients in the topsoil that had built up for centuries were soon depleted. Farmers found that beneath that surface layer the soil was acidic, and mainly sand. They tried enriching the land with animal manure, but there wasn't enough supply, especially since it required constant renewing. Crops began to fail. As the rising generation of farmers in the newly-created United States of America grew up, they began to leave New Jersey for better opportunities in the West. Politicians and newspaper editors lamented this exodus, but it was hard to blame young people for seeking their fortune elsewhere.

One newspaper editor remembered those difficult days:

Those who have lived in this part of the state [Cumberland County] for many years past, remember when it was customary to clear a tract of wood land, cart the wood to "Bridgetown"...trade it for flour and grain, which was imported from Philadelphia, and a few groceries....

After clearing a few acres it was skimmed over until its fertility was exhausted, and then turned out to commons; the occupant either engaged in chopping and carting wood, or pulling up stakes and moving to the "far west"--which western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio was then considered. The fertilizers produced in those times from the use of a few loads of hay carted in from the "mash" in the winter, was not sufficient to keep up the productiveness of the soil.[1]Some farmers didn't give up so easily. Rather than leave they tried to find a way to improve their land. Perhaps they could find some way put the right nutrients back into the soil. If they could, they would benefit from staying close to Philadelphia, which was growing dramatically in the new nation and was a good market for their crops.

Trying to Fix the Soil

One candidate for improving acidic soil was limestone. Farmers of the day didn't understand the exact chemistry behind it, but they knew there was something in limestone that helped: it "sweetened" the soil. In neighboring Pennsylvania they crushed the rock to get a calcium-rich powder to apply to their fields with good benefit. Another option was to burn the limestone to get quicklime, which could be mixed with water and applied, but this was tricky work and could be dangerous. However, these solutions could not work easily in West Jersey because the area had no limestone.

Another possible way to fix the soil involved seashells. Along the Delaware bay shore of the West Jersey seashells were easily found. Like limestone, shells are rich in calcium. Farmers tried burning the shells to create fertilizer. This showed some promise, but there simply weren't enough shells for widespread use.

But seashells were turning up in unexpected places. As West Jersey settlers dug wells they would find a layer of broken shells a dozen or more feet down. Underneath the shells they would find layers of different types of marl--sandy, crumbling deposits that varied in color from green and gray to brown and black. These layers also appeared as settlers cut roads into bluffs overlooking Mantua Creek, Raccoon Creek, Big Timber Creek, and the many other little waterways that wend their way through the area to the Delaware River. Some farmers began to try the different marls on their fields. Since they were found beneath layers of shells, maybe they were part of an ancient sea bottom, and if so, perhaps they would contain nutrients to help their farmlands.

Signs Point to "Yes"

Trial and error showed farmers that marl from this greenish layer of the belt made an extremely useful fertilizer. Poor, depleted fields became extremely productive after this marl was added. What was more, the effect did not diminish as the years went by. The "greensand" marl fundamentally transformed the cropland that received it.

|

| Greensand Marl. Photo courtesy of the Mantua Township History Museum. |

One correspondent wrote in 1833 of the accidental discovery of marl's beneficial properties and the success local farmers were having with marl in the northeastern part of the state:

I have, according to promise, collected a few facts upon the Jersey marl, as a manure, and I submit them to you for insertion in the New York Farmer.

Every person to whom I have applied for information upon this new and valuable article, speaks of it as possessing enriching qualities, truly surprising, and of more general value than any known substance at present in use for that purpose.

Its effect was accidentally brought into local notice about sixteen years ago, by a farmer, who, having a ditch dug in a meadow, had the soil scattered over the piece: the ditch or drain happened to cut a vein of this marl, and the produce of the meadow was three-fold the ensuing season, upon the spot where the marl was scattered.[3]Geologists examined the greensand marl farmers were pulling from the ground. They found that it contained three key soil components that are severely depleted by growing crops: Calcium-rich lime, phosphorus in the form of phosphoric acid, and potassium-rich potash, found in the small grains of glauconite that gave the marl its greenish tinge. Taken together these nutrients helped "fix" the soil and balance its pH level.

Not only was greensand marl effective and long-lasting, it needed no special preparation--farmers could simply dig it out and put it on their fields. This involved a lot of labor, but a farmer with accessible marl on his property could use post-harvest and pre-planting down-time to get the work done.

In the 1830s greensand marl was being tried by some farmers, and in the 1840s it was becoming widely accepted as an important fertilizer. Farmers in northeastern New Jersey, other midlantic states, and in the coastal south were trying it and also finding success. But the best marl seemed to be in West Jersey. Not only was it the most effective type of greensand, there seemed to be no limit to the supply underground--in some places the greensand marl layer was over sixteen feet thick. The only things keeping more farmers from using marl were: 1) The labor of getting the marl out of the ground, and 2) Moving the marl to farms that were miles from a good marl source.

Getting At the Marl

The easiest way to extract marl was to find a bluff or small cliff were it was already exposed, remove the layer of earth above it, and then dig the marl into a wagon and haul it away. The top layer of earth could then be put back in the hole made by removing the marl. This process of course worked best when the overlying earth was only a few feet deep.

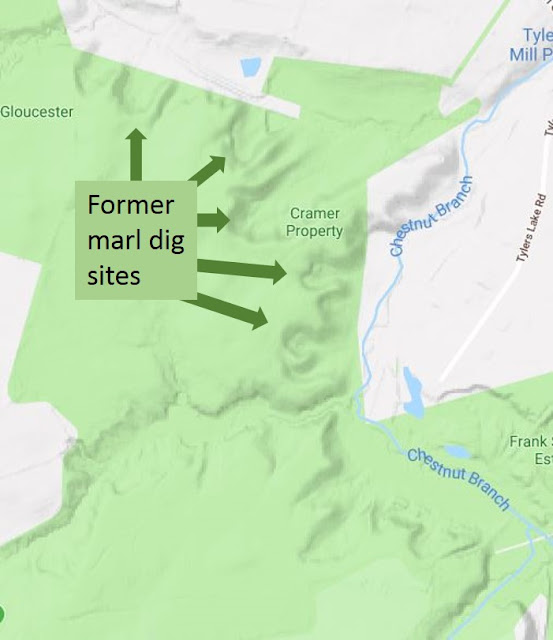

As mentioned above, valleys created by West Jersey creeks were a prime location for finding marl, and several farmers along the Mantua Creek and its tributaries began digging pits. Some began selling marl to neighboring farmers, or organizing with neighbors to work a marl pit together. In the following topographical map of the present-day Ceres Park area it is easy to see hollowed-out cliffs where marl was once dug along the creeks.

|

| Traces of marl diggings from the 1800s can be seen today in the heights above Chestnut Branch near Ceres Park. Courtesy of Google Maps. |

About 1840 unidentified farmers began to dig marl out of a hillside at the location that is now Ceres Park. The 1849 map below shows the spot with the label "Marl Pits." Today, Emerald Lake is at this spot.

|

| Vicinity of present-day Ceres Park area from an 1849 map of Gloucester County.[4] |

For reference, Clark's grist mill and sawmill on the map are at the corner of what is today Tyler's Mill Road and Main Street, Barnsboro. Notice that Lamb's Road, New Street, and the railroad had not yet been built. What we today call Chestnut Branch was then known as South Branch. Of the three lakes along that creek on the map, only the one by T. Carpenter's sawmill (Alcyon Lake) still exists.

The pit on the map was later purchased by David Marshall, owner of a large pit complex on the Big Timber Creek in Blackwood. He had become an expert on marl excavation and had high expectations for this site, especially if a railroad were to open nearby.

Getting Marl to Market

Digging marl was a physically demanding task, but in the early 1800s moving the excavated marl over distances was even more of a challenge.

Water transportation, used for so much in those days, made little sense. While marl was often found along creeks, it was mainly in the upper valleys where boats could not navigate. Marl pits dug close to the tides of the Delaware River would simply flood.

Horse-power was the only real transport option, and moving enough marl several miles to treat an entire field one wagon-load at a time was not practical. One agricultural authority of the day explained it made more sense for a farmer to buy land near a marl source and start a new farm there than to try to bring faraway marl to fields he already had.

But things were changing. The steam-powered railroad was making a name for itself, and New Jersey was at the forefront in developing this technology. The Camden and Amboy line, completed in 1830, was one of the first in the nation. It connected East and West Jersey, allowing passengers much faster travel between New York City and Philadelphia.

Some businessmen saw railroads as an opportunity for transporting marl. In 1836 the Monmouth and Middlesex Agricultural Rail Road was chartered in northeastern New Jersey, designed specifically for the task. An 1837 newspaper article described the vision of its founders:

These will be strictly agricultural rail roads, and the transportation of the valuable marls will furnish the largest item of their income.[5]By the 1840s the Monmouth & Middlesex was a success, causing investors throughout the state to raise their eyebrows.

In April of 1852 a group met in Salem to begin making the case for a railroad in West Jersey.[6] Enthusiasm for the project ran high, and things began to move quickly. In February of the following year a group of West Jersey businessmen obtained a charter for the West Jersey Rail Road (WJRR). Four months later the group commissioned William Cook, a general in the New Jersey Militia and the chief engineer of the Camden and Amboy Rail Road, to make a preliminary survey of the route.

The group's plan was to connect Camden and Cape May, delivering marl to farming communities all along the way. If business proved good, they would add lines to Salem, Bridgeton, and other West Jersey Communities. Providing transportation to the shore for vacationers was a secondary goal.

The company began by laying track along the old right-of-way of the defunct Woodbury & Camden railroad, which had not operated since 1840. While they worked on this section, other companies began building railroads that eventually become part of the WJRR. One group laid tracks connecting Millville with Glassboro. Another worked on linking Cape May to Millville, but ran out of funds before finishing.

By 1857 the WJRR had finished the Camden to Woodbury section. By 1861 its tracks reached south to Glassboro and linked up with the Millville & Glassboro line. It was now possible to transport cargo all the way from Camden to Millville by rail. With the railway moving ahead, it was time to think about getting the marl to the railroad.

The Political Angle

During this time New Jersey politicians had taken up the cause of marl transport by rail. They wanted to build business. They wanted to reverse the trend of farmers leaving the state for the West.

They also wanted to make useless land into productive (taxable) land. They pointed to millions of unused acres, much of it in Gloucester, Cumberland, and Salem counties, that could be made useful cropland by applying marl delivered by rail.

By common consent, Agriculture is acknowledged to underlie all the other pursuits of life. We often boast of the prosperity of our Commerce and Manufactures, but they would soon languish without a prosperous Agriculture. As legislators, our first duty should be to advance this great interest as rapidly as we have the power....

Judging from the abundance of the resources for improvement within our own borders, we anticipate a brilliant future. We believe that a very large portion of the 2,340,296 acres hitherto unproductive, can soon be made to yield valuable crops....

Resolved. That in the opinion of this House, the Agricultural interest of the state is of the first importance, and is deserving of the fostering care of the Legislature, and should have extended to it every facility of transportation, both for its manures and products, that favorable legislation, capital and enterprise can jointly afford.[7]

The Marl Rail Road

On March 6, 1863 a group of West Jersey Rail Road directors joined other interested businessmen to create the West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company. Its headquarters were in Woodbury at 17 Cooper Street. John Voorhees was the agent and general supervisor. David Potter, a founding director of the West Jersey Rail Road and general in the Cumberland County Militia, was president. T. Jones Yorke of Salem County, another founding WJRR director and the driving force behind the Salem Rail Road, was secretary/treasurer. Also on the board was David Marshall, the marl pit expert and owner. This new company would be responsible for getting the marl out of the ground, onto the rails, and to the customer.

The group arranged a long-term lease with company director David Marshall for 250 acres, including the marl pit that is now Emerald Lake at Ceres Park. In 1867 they also leased the adjacent pit of Richard and Joseph Ware, which included what is now the park's Crescent Lake. Both pits tapped into the same layer of greensand marl, an enormous deposit that had already become known by local farmers for its excellent properties.

We understand that the West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company has succeeded in making arrangements with Mr. Richard M. and Jos. C. Ware, to take the entire control of their extensive Marl Beds in Gloucester County, and are making the most gigantic arrangements for delivering it in all parts of New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware.

This Marl is unsurpassed in New Jersey, and is the most inexhaustible of any beds in the State.[8]West Jersey residents were interested in this enterprise. The local press described it as a heroic effort that would benefit the whole region and even beyond.

|

| News article in the West Jersey Pioneer.[9] |

The company had bought land on both sides of the West Jersey line near what is now the Lambs Road railroad crossing. There they built an engine house, repair shop, and depot. They laid track running a mile and a quarter out of the south end of Marshall's pit and up to the West Jersey line. As the map below shows, the track running from the pits crossed the roads close to the present-day intersection of Lamb's Road and Main Street. The company built housing for workers along Lamb's Road. People began calling the area surrounding the pit "Marlboro," and the company called its depot "Marlboro Station."

|

| An unidentified map from about 1876 showing the "Marlboro" section and the railroad connecting the pits to the West Jersey line. Photo courtesy of the Dolores Allen Historical Library. |

Much has changed over 15 decades, but a topographical map of the same area today still shows traces of the connecting railroad bed heading out of what is now Emerald Lake in the direction of the the Main Street/Lamb's Road intersection.

|

| Current map of the Ceres Park area showing evidence of rail line from the marl pit to the WJRR. Courtesy of Google Maps. |

The company impressed the public with the scale of its operations and with its efficiency at extracting the marl. An early visitor to the site reported:

The pits, as they are now opened, present an enormous chasm. The locomotive takes down a long train of cars and places them in the pit, where an active gang of pitmen quickly fill up the train, when it is taken out and off to market.

Thirty men on an average are busy all the time in pits, removing the overlay or earth covering, digging the marl out, etc. The facility with which these operations are done is wonderful. But with a locomotive engine in a marl pit, what may they not do?[10]

When William Came Marching Home Again

As the West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company was setting up operations the American Civil War ended. Soon thousands of New Jersey men were returning home from service in the Union Army. One of the most prominent of these was William Joyce Sewell, who had been twice wounded while leading brigades of New Jersey troops--once at Chancellorsville and once at Gettysburg. In 1866 he was made a brigadier general in recognition of his valor.

|

| General William J. Sewell, Director of the West Jersey Rail Road. Photo Courtesy of Findagrave.com. |

Upon returning home Sewell took a position as superintendent of the West Jersey Rail Road. He was New Jersey's most prominent war hero and many chances for leadership were probably available to him. The fact that he chose this one shows the new company was seen as an outstanding opportunity.

The West Jersey Railroad has commenced the transportation of marl to the country along the line of that road, and of the Millville and Cape May roads, and the demand is such to warrant them in preparing for an annual sale of 100,000 tons. In a very short time they will be prepared to supply that amount.

Lands that thirty years ago were useless and abandoned, are now teeming with abundance from the use of this fertilizer alone.[11]The West Jersey Rail Road had completed the track to Cape May, and the southern railways merged into the company. It soon added lines to Swedesboro, Bridgeton, and Salem--all passing through agricultural land that needed marl. By 1869 the expanded network was extensive, linking Gloucester, Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May counties.

Roaring Out of the Gate

|

| A West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company advertisement.[13] |

Within two years of beginning operations the West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company had passed seven competing firms to become the biggest seller of greensand marl in New Jersey. Dickinson Brothers had large operations in nearby Woodstown, but was limited because it had no railroad access. Even the Squankum and Freehold Marl Company, which had been the first to transport marl by rail, was left in the dust by West Jersey's extensive rail network.

A key reason for the success of the enterprise was the close connection between the West Jersey Marl and Transportation company and the West Jersey Rail Road. The transportation company's first leaders came from railroad leadership. The transportation company used this relationship to keep competitors from making deals with the railroad, and this allowed them to maintain the prices they were charging for the marl. The railroad in turn benefited by having a high volume of marl to distribute, in effect a guaranteed source of freight business. This special relationship continued through the years, as the following newspaper advertisement from 1875 shows: a board meeting of the transportation company was to be held at the railroad superintendent's office.

|

| From the West Jersey Pioneer.[14] |

Not everyone was happy with the special relationship between the Marl & Transportation company and the Railroad. Some of those who lived farthest from the pits, and therefore paid a much higher price for marl, thought it improper. In 1868 some who felt this way tried to organize a boycott. They wanted other marl providers to have access to the West Jersey Rail Road's network, bringing to bear competition that would lower prices:

|

| From the West Jersey Pioneer.[15] |

The proposed boycott seems not to have taken hold. The company's sales in the late 1860s were so strong that the sky seemed the limit. But circumstances would force the company to revisit its pricing policy just a few years down the road.

Meanwhile, the company could set its own price, and the demand for marl was strong. Experts were predicting the company would soon be selling 100,000 tons of marl a year. To do this it would need to 1) develop additional sources of marl and 2) extend its reach to new markets.

For the additional marl, the directors turned their eyes in the direction of the large pit owned by the Heritage family not far from Barnsboro Station, which today is called Sewell. The Heritages were competitors. They had a large, well-known pit and wanted to distribute their marl on the West Jersey Rail Road. It was alleged that they offered to put in a set of tracks accessing the pit at their own cost--but the Marl & Transportation company did not want competition, so the WJRR refused the offer.[16]

The Marl and Transportation Company began carefully exploring the land between Heritage's pits and their own--the area that is now home to the Snowy Owl, Gray Fox, and Buckingham Village neighborhoods. Much of this property belonged to the McFarland family, who were interested in selling it. They advertised it as a "well-known marl farm."[17]

In 1868 the company bought the McFarland property and some adjoining land. Its new holdings covered everything in the current town of Sewell south of Warren Avenue, on both sides of the tracks. There the superintendent planned to expand the marl pit dramatically and install a new set of rails to connect it to the main WJRR line.

The company also partnered with other railroads to get their marl into new markets. It made an arrangement with the Camden & Amboy Rail Road to use its own trains on the C&A tracks to send to customers in North Jersey. It also delivered product on the Pennsylvania Reading Rail Road to farmers in Pennsylvania. In addition, the company opened a depot in Westville. Here it could transfer marl from its trains into barges for delivery in Delaware and Maryland. By the 1870s, the company had hired agents in those far-flung places, and was advertising in newspapers there. The following ad is from the Middleburg Post.[18] Middeburg is northwest of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

|

| Company advertisement in the Middletown Post, a Pennsylvania newspaper. Middletown is northwest of Harrisburg. |

Life in the Pits

By the mid-1860s the West Jersey Company's marl pit in Marlboro bustled with activity. A newspaper reporter to the site in 1868 filed this report:[19]

On entering the pits a busy scene presents itself. Deep down may be seen a long train of cars with a locomotive at the head of it, and sometimes two of them. A large number of hands throwing up marl from a lower depth, and others filling cars. This operation occupies but a little time. A train carrying 200 tons can be loaded in an hour.

On a higher level, on the top of the marl deposit may be seen another train removing the over layer or surface earth. The excavation is now very extensive. As the over lay is removed it is thrown into the pits from whence the marl has been got out.

And so the work goes on--uncovering, digging the marl, and filling the empty pits. The over lay at present is about 12 feet deep, and the depth of the green sand marl is about 16 feet. At the time of our visit, there was a bank of marl uncovered at that depth which will yield over 20,000 tons.Most of the workers in the West Jersey company's pits were Irish immigrants. The image below from the 1870 census shows the record of two typical workers, James Tuohy and Michael Carry, living together in a Mantua Township household along with their families. Michael was likely the son-in-law of James.

|

| Record showing Irish immigrants in 1870 US census "working at marl pits." Courtesy of Ancestry.com. |

The marl pit scene shown below is from the West Jersey Marl operations at Sewell, between what is now the Target and the Lowe's parking lots. No photos of the Marlboro pits have emerged, but the process used was similar, and the equipment may be the same. The photo shows workmen posed by the cars that carried marl up and out of the pit. They dug down the wall of marl with simple shovels and loaded it into the cars. As they completed one section they re-positioned the tracks to keep them near where they were digging. To the right of the tracks you can see where they were laid previously.

|

| Workmen in the Sewell marl pit of the West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company, 1888. There are no known photos of the company's Marlboro pit operations, but they likely would have looked similar to those in this photo. The man in the inset is the company's supervisor, John Voorhees. Photo Courtesy of the Dolores Allen Historical Library. |

Working the pits was hard physical labor and dangerous, given the sheer volume of earth the workers were moving. Excavating the marl could make it unstable and accidents could happen, as the following article details:

On Tuesday, the 7th inst., while engaged in the excavation of marl from the beds of the New Jersey Marl Co., at Marlboro, a man named Patrick ? was severely injured by the caving of the earth, breaking three ribs and shattering the collar bone. Dr. Glanden, of Mantua, was called and rendered professional aid, who, together with the consulting physician, Dr. Henry C. Clark, performed the operation of removing a part of a rib which penetrated his chest. The patient is now doing well.[20]

Marly Bones

Cope and Marsh had been on friendly terms, but a visit to Marlboro changed things. Cope hosted Marsh, who was visiting from Connecticut, and took him to see the pit that had been the source of aquilunguis. In the course of the visit he introduced Marsh to John Voorhees, the West Jersey Marl company's superintendent. Before returning to Connecticut Marsh surreptitiously went back to the pit and spoke with Voorhees in private. Voorhees agreed, for a fee, to send any interesting new fossils on to Marsh at Yale without notifying Cope. When Cope learned about this he was furious. He and Marsh became bitter professional enemies and remained so for the rest of their lives.[21]

Trying to Stay Dry

The Marshall pit was already large by the time the West Jersey Company took over operations. But with the high-tech rail cars in play it was getting bigger much faster. This meant more surface area on the sides of the pit, and more water seepage, which was still carried away by a drain trench to the nearby Chestnut Branch. But by now the drain trench was only a few feet higher in elevation than the creek, and the diggers had not reached the bottom of the layer of greensand. If they excavated any deeper the pit would be lower than the drain.

The company commissioned a surveyor to take elevations at several key points in the area. A look at the locations they measured shows they were thinking about how to drain water from marl pits:[22]

Lines 8-10 show the elevations of the top and bottom of the greensand marl layer in the company pit. Line 11 in effect shows the highest level of the lake at Clark's dam, into which the nearby Chestnut Branch flowed. A comparison of lines 10 and 11 highlights the company's dilemma: if they fully excavated the Marshall pit, its bottom would be at least a dozen feet lower than the creek. A drain into the creek would be out of the question. How would they remove the seeping groundwater?

The company decided to keep digging deeper. To address the water seepage, they planned a two-step solution. For the immediate future they would use a steam-powered pump to remove the water from the pit and into the creek. As a long-term measure they would build an underground drain that would empty into Chestnut Branch over a mile downstream from the pit, bypassing Clark's mill and its lake. This would be an ambitious project, as one newspaper account described:

To facilitate their operations and drain their pits of the rapidly accumulating water in them, the company have to maintain expensive hydraulic works. A seven horsepower engine is kept at work day and night on a seven inch pump. A five horse engine and another pump are kept in reserve in case of necessity.

To avoid this expense, the company are now laying a drain from the head of their pits to the head of Jessup's mill pond, a distance of 6200 feet, with a fall of one inch in 100 feet, at an average depth of about 12 feet below the surface.

The drain is to be made 14 by 24 inches in the clear, which will require 100,000 feet of lumber--30,000 of which is to be Georgia fat pine plank, the rest hemlock. This will, it is believed, drain the pits of surplus water. This will not interfere at all with the natural flowing stream.[23]The "head of their pits" must mean the northernmost part of the Marshall pit, now Emerald Lake. The "Jessup's Mill Pond" was behind a dam long since gone that created a lake where Center Street in Sewell currently crosses the Chestnut Branch. The route of the proposed drain is not clear. The Historical Commission would be happy to hear from anyone with information on this topic.

The Creek Rises

Even today the waters of Mantua Creek and its tributaries will overflow their banks when prolonged rain hits the area. But in the 1800s there was more potential for flood damage, due to the mill dams in the area. The sawmill dam at what is now Alcyon Lake, not a mile Chestnut Branch from the West Jersey Company's marl pit, was a potential threat to the operation. If the dam washed out--or even if it released extra water to avoid a dam break--the overflowing creek might spill into the pit, creating vast pools of water that would be hard to pump out.

This is just what happened. In May of 1866 a major rainstorm damaged the upstream dam and the creek flooded into the pit. This caused marl-digging operations to go off line temporarily, but the water was gotten out within a few days. Just over a year went by and then, in August of 1867, a more severe storm hit. Every dam on the Chestnut Branch gave way. The creek poured into the pit, which by now had been dug to a lower level. A newspaper account described:

On the branches of Mantua Creek every mill dam has been swept away. Tucker's or Iszard's, Stoke's and Packer's, Clark's and Jessup's, are all gone. At Clark's Mill, the Glassboro Turnpike was washed away a space of 50 feet long and 15 deep. The water wheel at Jessup's Mill lies a great distance down the meadows.

The Marl Pits of the West Jersey Company were of course over flowed, doing very serious damage to the works and stopping their operations.[24]The company could not afford to repeat the weeks of downtime and repairs to operations that followed this flood. They needed output! A newspaper reporter described the pressure on the company from the high demand for greensand marl:

We made, a few weeks since, a visit to the [West Jersey] marl pits, and were pleased to note the progress of the operations, and the improvements and facilities employed in getting out this great natural fertilizer. An immense amount has been sent to market this year, and the company's means are taxed to meet the large daily orders received.[25]To protect the operations the company built a protective earthen berm between the creek and the pits 60 feet wide and 20 feet high. The berm was created using the overlying dirt removed to get at the layer of greensand marl.

The berm seems to have done its job well. Although it could not entirely prevent a flood, it did minimize the damage. In September of that fall, the Constitution reported:

We were visited on Thursday night with a rain storm which cause a widely extended and very disastrous flood, even more so than the flood in August of last year....The head waters of Mantua Creek were also so swollen that Wyne's dam (late Packer & Stokes) broke, inundating the West Jersey marl pits, but doing no damage there.[26]What is left of the berm forms the western boundary of Emerald Lake today. Ironically, instead of keeping the water out it now keeps the water in--the surface of Emerald lake is significantly higher than the nearby creek. A walking trail runs along the lake on top of it.

|

| Looking westward across Emerald Lake at the remains of the earthen berm built to keep water out of the Marshall marl pit. Photo courtesy of the Dolores Allen Historical Library. |

A Drain on Company Resources

On Wednesday last, while the men employed in excavating the underdrain from the West Jersey Marl Pits were at work a short distance above Clark's Mill, blasting some rocks, a fearful accident occurred. The excavation was here 17 feet deep. Three drills in a line a few feet from each other had been made and charged, and the fuse ignited.

James Bogart, observing that the middle one did not seem to be burning properly, went to it, and when just in the act of stooping over it, it exploded, throwing him down with his head over the first, and his lower extremities over the third charge.

The boss, Mr. Carey, called to the men nearest on the ground above to rescue the man before they exploded. The danger was so imminent they hesitated, when he jumped down himself, and seized the almost inanimate body, weighing about 175 pounds, and bore it off a few seconds before the remaining discharge exploded with great force, and was unhurt.

Bogart, but for this daring act of his deliverer, would have been blown to atoms. He was very much injured about the head. The tube from the charge appeared to have entered the under part of his chin and passed out through his cheek. His physician is not without hope of his recovery. [27]

(Perhaps the heroic boss in this story was the "Michael Carrey" from the census record in the previous "Life in the Pits: section.)Danger went with the territory, perhaps, but what really troubled the company was cost. Cost in the form of materials and manpower, the cost of operating the steam pump for longer than expected, and the opportunity cost of marl not dug and sold because water in the pit hampered digging.

The great underdrain has proved a more formidable undertaking than was anticipated. Its whole length from the outlet to the mouth of the pits, is 5700 feet, in some places 28 feet deep; and what was not expected, 2000 feet of the drain had to be blasted to a depth of 4 feet. This has added greatly to the cost, as well as retarded the work.

400 kegs of powder were used in the blasting, which increased the cost about $8,000. The whole cost will be about $20,000. The blasting here alluded to, may strike some of our readers with surprise not thinking there is any stone in these parts to blast. There is however, a hard marl rock formation lying at a certain depth, which has to be drilled like any other rock, and which the force of powder alone can remove.

The work will be done by the last of next month. It will drain the pits to a depth of three feet.[28]But the work would not be done by the end of the year, nor of the year following. The challenge and expense had proven too much. The company had by now purchased the McFarland farm and in the coming years would gradually move its marl mining emphasis away from Marlboro and toward what is today the Fossil Park.

Feeling the Pinch

Railroads across the nation changed ownership, merged, or simply faded away during this crisis. The West Jersey Rail Road was not immune. Valuable because of its network but financially hurting from declines in freight and ridership, it was bought by the Pennsylvania Reading Railroad. General Sewell survived the shakeup. He remained superintendent, but now operated the WJRR as a division of the PRR. The PRR, sensing brighter days ahead once the depression ended, renewed the WJRR's contract with the West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company.

The panic caused difficulties for everyone. Farmers had less access to credit, and at the same time less revenue, since their customers had less money to spend. In this new environment it was difficult to come up with the money to purchase marl for their fields--particularly if they lived a significant distance from the Marlboro pits and therefore paid more for delivery. For example, a farmer in Bridgeton paid 38% more for a load of marl than a farmer in Glassboro, and a farmer in Cold Springs near Cape May paid twice the price.

Five years into the depression the West Jersey Marl and Transportation was in a hard way with its marl business. A letter from its superintendent to the State Geologist's office described the company's position:

From J. C. Voorhees, Superintendent of the West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company

Dear Sir:--Our business has been small for the year 1878, and I feel very much ashamed of it. I could not do any better. Our farmers are very much discouraged. The price of grain, &c., is very low. Very few farmers have made both ends meet....Farmers complain very much of the price of marl, and think it ought to be lower.

|

| From The Annual Report of the State Geologist of New Jersey.[29] |

Marl sales in 1878 were only 1/5th what they had been ten years previously. This was not a sustainable trend.

Not with a Bang...

It is not clear when it happened, but at some point the West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company gave up on the Marlboro pits. It may have begun as a temporary shut-down during the Long Depression as the company was squeezed for money due to sluggish marl sales. Work on the underdrain was suspended. Mining crews were reassigned to the new marl pit a couple of miles to the northeast, which now had its own office, worker housing, and set of tracks connecting it to the WJRR.

The steam pump emptying the Marshall and pits either failed or was left idle. The Marshall and Ware pits began filling entirely with water.

(An aside: A local legend says an old steam engine was left behind in the pits, that the company couldn't get it out and decided to leave it where it still lies beneath the dark waters. The story seemed spooky to me as a boy, and I have wondered at it since: Why would a company that was a going concern leave to rust something as valuable and portable as a locomotive? After all, even if they scrapped it they would get something for it. Is it possible that the source of the legend is the old steam engine that ran the pump to keep the water level down in the Marshall pit? I can imagine a piece of equipment like that left in the pit, particularly if it had been submerged as the waters rose.)

The Long Depression ended, and things looked up for farmers again by 1879. But although the West Jersey Marl Company had a new pit going well, and had even lowered the price of marl to help address customer concerns, its most productive years had passed. The main reason for this was a new type of competition offered by chemical companies, as one writer noted:

By 1880 the more concentrated chemical manures began to offer serious competition to greensand marl. Gradually the latter material, because of its bulky character and high cost of handling, began to shrink in importance until by the end of the century its use was practically discontinued. [30]General Sewell, after a stint in the U. S. Senate, would become a vice president of the Pennsylvania Reading Railroad, and finally, president of the new subsidiary West Jersey and Seashore Railroad, which concentrated on passenger traffic between Philadelphia and the Shore. He died two years later in 1901.

The West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company would survive (barely) into the next century, still supervised by the energetic Mr. Voorhees and now offering many kinds of chemical fertilizer.

In 1890 Superintendent Voorhees created a map of his company's new operations.[31] At the bottom of the map, he drew an arrow pointing in the direction of what was once Marlboro. His label read "R.R. to the old marl pits."

Year by year the forest began to re-establish itself at the future Ceres Park. The connecting railroad tracks were removed. Various ideas for the land were put forward; these are beyond the scope of this research. The trees grew taller and the pits turned into lakes. The noise and bustle were long gone. Gradually, Ceres Park became what it is today.

New Jersey becomes the Garden State

As our nation approached its 100-year anniversary in 1876 it was preparing to celebrate in a big way. A city of pavilions, houses, and showplaces was arising in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia, all part of the Centennial Exhibition. Here Alexander Graham Bell would show his new invention, and Thomas Edison would present. People would come from everywhere to honor the past and peek into the future.

Every state tried to put on its best, and New Jersey was no exception. So it was that among the technical displays and novelties the state also presented its garden produce.

Public perceptions of New Jersey were changing. Once seen as a barren peninsula between agricultural powerhouses New York and Pennsylvania, now it was becoming well-known for its outstanding farms. The state's market-garden produce (vegetables, tomatoes, squashes, etc.) was in high demand in New York City and Philadelphia, and New Jerseyans were proud of this.

|

| The New Jersey agricultural exhibit at the 1876 national Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia. |

The chart below helps demonstrate the facts behind this changing perception. It shows the value of market-garden produce before and after the West Jersey Marl and Transportation Company began operations in 1866. Between 1860 and 1870 the per-acre value of Gloucester County produce (the yellow column) quintupled. This extraordinary growth drove a doubling of produce value for the whole state (blue column).

New Jersey statesman Alexander Browning of Camden gave a speech at the Centennial's "New Jersey Day." He praised the state's farmers and their produce, pointing to its popularity in Philadelphia and New York--a topic that would have been laughable thirty years previously. According to historian Alfred M. Weston in his 1926 work Jersey Waggon Jaunts, Browning called New Jersey "The Garden State," and the name stuck.

While some have disputed that Browning himself coined this phrase (the printed version of his speech does not include it) the bigger point is that the name did stick--New Jersey had actually become the garden state.

Ceres was the name of the Roman goddess of agriculture. Perhaps as we walk through the quiet woods of Ceres Park and look out over its lakes we will take a moment to reflect on what happened here 150 years ago. Those who came before us, whether innovators, leaders, investors, diligent farmers, or immigrant manual laborers took what came out of the ground here and turned a sandbar state into a garden spot. May we take lessons for our own lives from their optimism, dreams, cooperation, and hard work.

-TD

1 James R. Ferguson in the West Jersey Pioneer, (Bridgeton NJ), 26 Nov 1864. Retrieved from the West Jersey Pioneer Collection in the Cumberland County section of the Historical New Jersey Digitized Newspapers, New Jersey State Library.

2 Potash in the Greensands of New Jersey, A U. S. Geological Survey report by George Rogers Mansfield. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1922. Page 3. Retrieved from US Government Publications.

3 D. A. Ames to Mr. Fleet in the New York Farmer, September 24, 1833.

4 Alexander C. Stansbie, James Keily, and Samuel M. Rea. A Map of the Counties of Salem and Gloucester New Jersey. From Original Surveys (Philadelphia: Smith & Wistar, 1849) [Library of Congress]. Retrieved from the Princeton University Library Historic Maps Collection

5 Agricultural railroad quote.

6 WJ&S Timeline 0836-1932 in the SJRail.com Wiki. Retrieved from SJRail.com

7 Report of the Committee on Agriculture (1865) in Documents of the Twenty-Second Session of the State of New Jersey, being the Ninetieth Session of the Legislature, (New Brunswick N.J.), 1866, p. 825-826. Retrieved from https://books.google.com

8 The Millville Republican, 1 May 1867.

9 The West Jersey Pioneer, (Bridgeton NJ), 2 Jan 1864. Retrieved from the Chronicling America online collection of the Library of Congress.

10 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), Jun 1867. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Page 189.

11 Report of the Committee on Agriculture (1865) in Documents of the Twenty-Second Session of the State of New Jersey, being the Ninetieth Session of the Legislature, (New Brunswick N.J.), 1866, p. 821. Retrieved from https://books.google.com

12 Map of the Rail Roads of New Jersey and Parts of Adjoining States (Philadelphia: J. McGuigan, lithographer, 1869). Retrieved from Rutgers University Historical Maps Collection

13 The West-Jersey Pioneer, (Bridgeton NJ), 2 Nov 1866. Retrieved from the Chronicling America online collection of the Library of Congress.

14 The West-Jersey Pioneer, (Bridgeton NJ), 20 May 1875. Retrieved from the Chronicling America online collection of the Library of Congress.

15 The West-Jersey Pioneer, (Bridgeton NJ), 6 Mar 1868. Retrieved from the Chronicling America online collection of the Library of Congress.

16 Anonymous letter to the editor entitled Marl in the West Jersey Pioneer, (Bridgeton NJ), 26 Apr 1867. Retrieved from the Chronicling America online collection of the Library of Congress.

17 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), 20 Nov 1867. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Page 190.

18 The Post, (Middleburg PA), 19 Sep 1878. Retrieved from the Chronicling America online collection of the Library of Congress.

19 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), 18 Nov 1868. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Page 189.

20 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), 15 Mar 1871. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Page 191.

21 Haddonfield and the 'Bone Wars': 19th Century Paleontology in Camden County. Hoag Levins, a cyber feature on the author's website.

22 Elevations about Barnsboro

23 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), Jun 1867. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Pages 188-189.

24 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), 21 Aug 1867. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Page 100.

25 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), 18 Nov 1868. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Page 189.

26 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), 9 Sep 1868. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Page 101.

27 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), 22 Jan 1868. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Page 191.

28 The Constitution, and Farmers' and Mechanics' Advertiser, (Woodbury, NJ), 18 Nov 1868. Quoted in A Bicentennial Look at Mantua Township, The Mantua Township Bicentennial Committee and The Mantua Township Lions Club, Page 189.

29 Geological Survey of New Jersey: Annual Report of the State Geologist for 1876, Pages 118-119. Retrieved from Google Books.

30 NJ Agriculture, Apr 1919, Page 4.

31 Potash in the Greensands of New Jersey, A U. S. Geological Survey report by George Rogers Mansfield. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1922. Page 46.

32 Centennial Photographic Co.. New Jersey State Building. [Albumen Prints]. Retrieved from the online site of the Free Library of Philadelphia.